Copyright Lessons From The Masters: What Taylor Swift Losing Her Music Should Teach Every Entrepreneur

If you’ve ever created anything within your business (literally anything tangible- a blog post, a photo, an online course, a template), then you must be aware of the copyright rights available to you….and those easily stolen from you. It’s not an option; it is requisite information for any founder to know; if anyone steals your work, you cannot take action if the copyright is not registered.

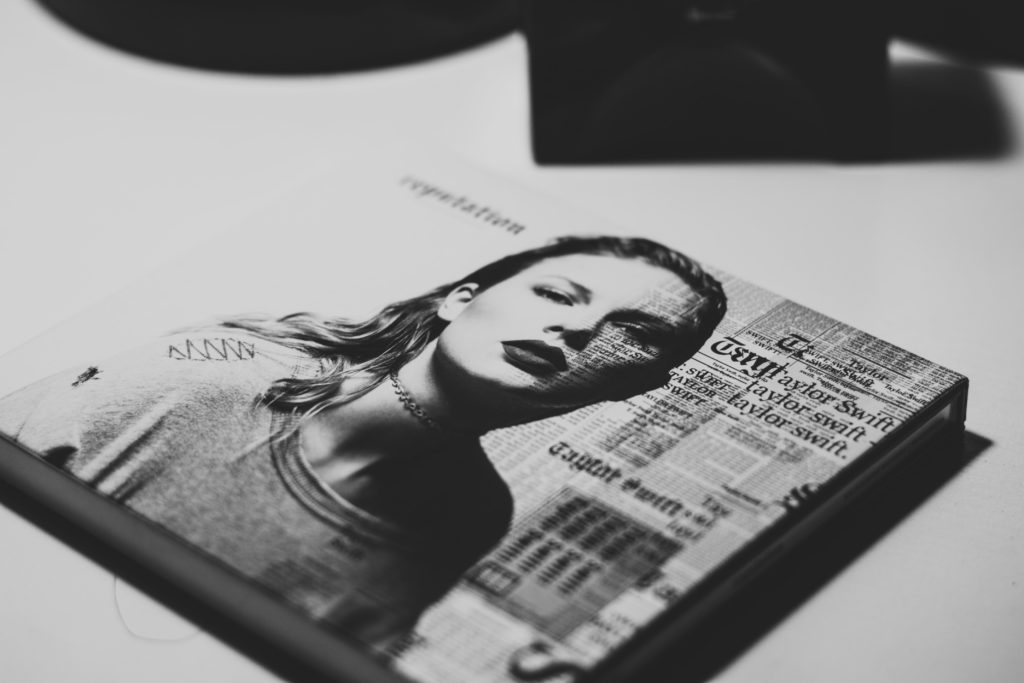

Arguably, the best example from the last half decade is Taylor Swift, and the legal (and PR) battle you’ve seen play out on an international stage. What can entrepreneurs and creators learn from this move, that. Regardless of fandom or not, lawyers and business strategists have dubbed it as brilliant, which means it’s worth studying.

As every client of our firm has heard us say, all business decisions must be examined through the lens of legal, and vice versa. Swift’s decision to re-record her albums is a brilliant stroke at both. But why is she doing this?

The business considerations are easy enough to spot. She’s invited her fan base into the story predicated by injustice, and allowed them all to help participate as she rectifies an unjust situation. As a business owner, this move is simply brilliant- by creating this story, not only is she re-activating her existing fan base, or even creating a new fan base; she’s capitalizing on the leverage she has now as one of the most successful artists of today to re-adjust the scales of an agreement she signed as bright-eyed child, while also re-creating music that this time, she owns. From a legal perspective, she’s exposing realities of copyright law, and methods to be advantageous as a creator.

Creator v. Owner

Understandably, in Swift’s case, there is confusion in the general public that the writer, artist, and performer of a song would “own” this song. However, this is not how copyright law works. In the same way that someone’s writings and photographs, that does not necessarily mean that the writer or photographer owns the book.

Copyright law is centered around rules formed by both contracts and copyrights.

Copyright Law Fundamentals

A copyright is technically formed as soon as the “expression of an idea in tangible form.” More bluntly, as soon as your work has been captured in some sort of tangible form and it can be reproduced, copyright law protects it. However, that work must be registered at the copyright office in order to be enforceable against infringers.

The owner of the copyright has the right to do the following:

- Display the work

- Distribute copies of the work

- Perform the work publicly

- Reproduce the work

- Make derivative works

- (and in the world of music): Perform copyrighted sound recordings by means of a digital audio transmission

Different types of copyrights carry different types of rights that must be considered (and specified in a contract). For example, in the world of music, there are generally two types of rights: musical compositions and master (sound recording). Generally speaking, the former is typically the lyrics to the song, the music, or both. The latter is the recorded performance of a song.

The Role of Contracts (& Why Every Creator Should Care)

Here’s why, as any type of creator, you actually do care about the legal precedent being set by Swift, irregardless of if you are a self-proclaimed “Swiftie”. In Swift’s case, she owned the “musical composition” to her songs, as she wrote the songs. However, her record label owned all of the Masters to her songs. It did not matter that she was the performer of the songs.

To any creator (anyone creating videos, online courses, writing articles, taking photographs, etc) here’s what’s interesting: the difference between being the author and the owner. As the creator, you initially own the content as soon as it is created. But if you agree in writing that someone else acquires those ownership rights, you just become the author.

In most contracts, you’ll see this worded as a “work made for hire”.

Work for Hire

Simply put, this occurs when a creator is hired to create a work within the scope of the specific project. An exception to this rule occurs in true employment agreements (not independent contractor agreements): if the hire is an employee, and the creation is within the scope of their employment, the creator is automatically a work for hire.

Because Swift was an independent contractor, she had to have transferred, or assigned her rights to another in some form of an agreement.

The Legal Implications Of Assigning Away Ownership Rights

Common practice in the music industry, Swift assigned away her rights, in exchange for the record label to promote her, pay her, and roll the dice on her success. Obviously, they won out on that deal! By transferring ownership to her record, Big Machine, she also gave them the right to sell her music to another party, which is exactly what happened in 2019.

Because Swift was no longer the owner of the original audio recordings from which other copies were made, Big Machine had free reign over her Masters, album art, and videos. She had no control over whom they were sold to. In 2019, Scooter Braun’s Ithaca Holdings agreed to acquire Scott Borchetta’s Big Machine Label Group. Once again, ownership of the Masters of Swift’s first 6 albums were sold, outside her control. This is when the feud hit most of our radars, when Swift came out and said, “Never in my worst nightmares did I imagine the buyer would be Scooter.” She also claimed that Braun wouldn’t let her perform her old songs, and that her MAsters were being held ransom in exchange for her signing another contract. Whether this is true or not is a conversation for another day, but worth mentioning here because again, every strategic business decision must consider both the legal and business implications.

The Loophole

Legally, there wasn’t a loophole in the agreement to transfer Swift’s rights…but there absolutely was a “business loophole”. And on that loophole, she capitalized. First, her original contract contained language limiting her ability to re-record old music….which expired in November 2020. Additionally, because she had written all of the songs on those first 6 albums, she owned the “sync rights” we mentioned above. This is critically important for two reasons:

- She held the “synchronization license” (ie, the songs’ ability to be used in advertisements, etc), and can therefore essentially bar anyone from profiting off of those original Masters

- Depending on the next deals she could sign, she could theoretically “replace” her old music with re-recordings

Which is exactly what she did, capitalizing on the marketing opportunities and highly-engaged fan base, who were just as excited to hear the re-recordings as the “old recordings” (often, because Swift has released “vault” tracks along with each, etc).

Always Understand The Contracts You Sign

For business owners, Swift’s case serves as a potent reminder to always read and understand any agreement you sign. Unless you intend to assign your intellectual property rights away, don’t let assignment language slip into agreements.

At the end of the day, business is business, and while this may have been a standard agreement for her industry when she initially signed with Big Machine, circumstances change, and people change. Relying on relationships to remain unchanged is foolhardy- allegedly, Big Machine was sold to Ithaca Holdings for $300 million. That will (obviously) change the dynamic of a business relationship quickly.

The Takeaways:

- Authorship and ownership of copyrights are two different things. Ensure you maintain both

- Intellectual property law and contract law commonly intersect with one another. Always keep an eye out for language that transfers, or assigns your intellectual property ownership

- When working within the scope of an independent contractor or employment agreement, know at the outset whether your work is a work made for hire

- On the flip side, if you hire someone to create something for you, know that the creator must transfer their rights as “work for hire” to you

- Contractually, always ensure that you have language in your agreements protecting yourself from the unknown.

LEAVE A COMMENT

View Comments